Emotionally-focused therapy (EFT) has emerged as one of the most evidence-backed forms of couples therapy (Byrne, Carr & Clark, 2004). It is founded on the concept that marital distress results primarily from “ongoing absorbing states of distressed affect and the constrained, destructive interactional patterns that arise from, reflect, and then in turn prime this affect” (Johnson, Hunsley, Greenberg & Shindler, 1999, p. 68). Expression of primary emotions, such as sadness, shame and fear of abandonment, are encouraged in order to increase intimacy and affiliation in a couple and reestablish attachment bonds. This is done through “absorbing negative affect,” or focusing on the inner experiences and primary emotions of each member of the couple. (Johnson et al., 1999, p. 68). EFT also “targets rigid self-reinforcing interaction patterns,” and attempts to shift these interactions so that each member of the couple can express themselves in a way that will “prime bonding events” (Johnson et al., 1999, p. 68).

Theory Behind Emotionally Focused Therapy

EFT combines the teachings of the Gottman longitudinal studies, systems theory, the intrapsychic focus of psychodynamics, and the experiential focus of humanistic therapy (Johnson & Greenman, 2006). According to the Gottman studies (Carstensen, Gottman & Levenson, 1995), distressed couples are characterized by a proportionately greater exchange of negative affect to positive affect compared with nondistressed couples. The Gottman studies also found that “[n]egativity appears to be dysfunctional only when it is not balanced with about five times the positivity, and when there are high levels of complaining, criticizing, defensiveness, contempt, and disgust” (Gottman, 1993, p. 14).

Based on this understanding of the importance of affect in distressed marriages, an EFT therapist focuses on six core emotions: joy, surprise, fear, shame, anger and sadness. (Johnson, 2007). Each of these emotions has “a cue, a general instantaneous appraisal (negative/positive, safe/unsafe), physiological arousal in the body, reappraisal in which meaning is assigned, and a compelling action tendency that ‘moves’ a person to a particular response” (Johnson & Greenman, 2006). An EFT therapist draws out these core emotions, by using reflection and evocative questions about what the individual is actually feeling at present, which is sometimes called “mining the moment” (Johnson, 2007, p. 48).

By getting in touch with and expressing primary/core emotions, members of the couple are able to share and understand their intrapsychic experiences. Expression of these primary emotions in-session has been shown to increase affiliative responses from the other partner (Greenberg, Ford, Alden & Johnson, 1993). This increased understanding and affiliation in the relationship may even create a secure base for dealing with issues unrelated to the couple (Dessaulles, 1991; Walker, 1996).

Expression of these core emotions also draws attention to the negative reciprocal affect cycles that have been occurring. One common reaction to disconnection, for example, is for one partner to cling or pursue and for the other partner to distance or withdraw (Johnson & Greenman, 2006). Each of these reactions then causes the other partner to continue or amplify his or her reaction such that a negative affective cycle results. By focusing on the negative reciprocal affect cycle, the couple is able to understand the sequence that contributes to its distressed state and to create new ways of relating.

Process of Emotionally Focused Therapy

EFT is implemented in nine steps. The first four steps involve cycle de-escalation. The first step is assessment, when an alliance is formed and the main issues with the couple are discussed. The second step is cycle identification, when the negative interactional cycle is pointed out and discussed with the couple. The third step is accessing the underlying emotions that promote the negative interactional cycle identified in the second step. In the fourth step, the problem is reframed in terms of the cycle, emotions and attachment needs (Johnson et al., 1999, p. 70).

The next three steps involve changing interactional positions. The fifth and sixth steps include promoting and integrating “disowned needs and aspects of self into the relationship interaction,” and “promoting acceptance of the partner’s new construction of experience in the relationship and new responses” (Johnson et al., 1999, p. 70). In the seventh step, the partners are encouraged to express their specific needs to engage emotionally.

The final two steps involve consolidation and integration. New solutions to old problems are facilitated in the eighth step and new cycles of behavior are facilitated in the ninth, final step (Johnson & Greenman, 2006, p. 600).

Effectiveness of EFT

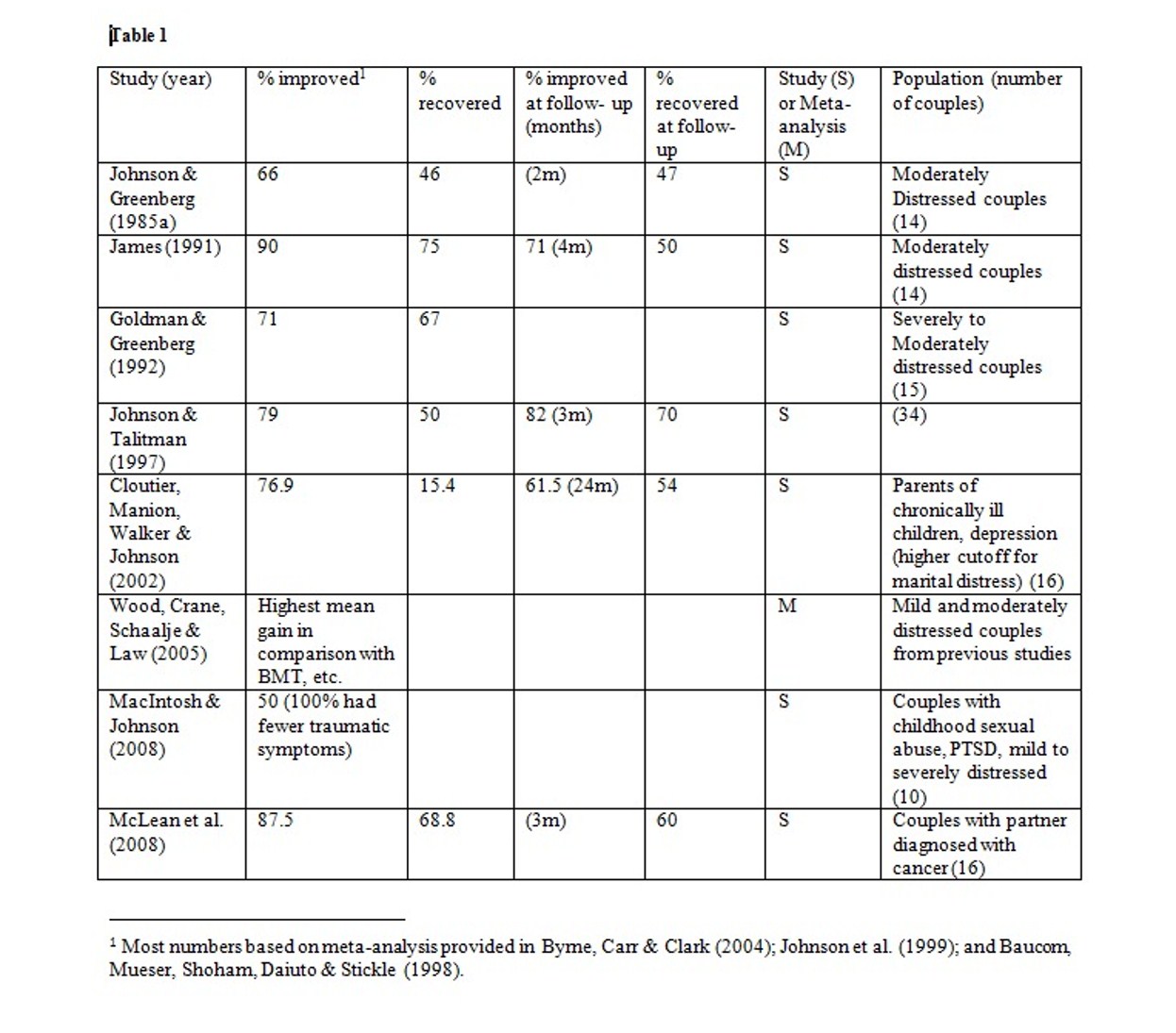

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of EFT to improve marital distress. A listing of some of these studies and meta-analyses is shown in Table 1:

As can be seen in the above table, EFT has had overwhelming success in clinical studies showing improvement in distressed couples. Most of the studies listed above measured the marital distress based on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (“DAS”) based on manualized procedures for EFT and included follow-ups several months after treatment.

In the Johnson & Greenberg study (1985), forty-five couples were assigned to either EFT, CBT or to a control group. Fourteen mild- to moderately-distressed couples were given pre-treatment assessment according to the DAS (Spanier, 1976) and then completed eight sessions of EFT with Masters- or Doctoral-level therapists. Participating couples had to be living together for at least one year, immediate plans for divorce/separation, no psychiatric treatment within the past two years, free of alcohol and drug problems, and at least one member of the couple rated below 100 (distress cut-off) on the DAS. The majority of the couples scored in the moderately distressed range at in pre-treatment.

Johnson & Greenberg (1985) found that the group receiving EFT had a mean pre-test DAS of approximately 92 and a mean post-test DAS of approximately 114.5. This was significantly higher than the “problem solving” group, which had a mean post-test DAS of approximately 101, although the mean pre-test DAS of this group was slightly lower – approximately 90.5. The control group had no improvement after the waiting period. The EFT group also had significant gains over the control group for goal attainment, and significant gains over both the control group and the “problem solving” group for intimacy levels and target complaint reductions. After a two-month follow-up, the mean DAS of the EFT group lowered to approximately 114. Although this study appears to show that EFT may be effective in treating distress, it should be noted that the study had a relatively small sample size and focused largely on moderately distressed couples. A longer-period follow-up would also be desired.

In James (1991), fourteen couples were put in each of three groups. Each group was treated with either enhanced EFT, EFT with communications training, or put in a control group (Baucom et al., 1998). Post-treatment DAS results showed significant improvement for those couples receiving both enhanced EFT and EFT with communications training. Communications training did not appear to improve the DAS results. Although the results of 90% of couples improving are staggering, it is worth noting that 50% of the waitlist couples improved without treatment.

The Goldman & Greenberg (1992) study involved forty-two distressed couples, of which fifteen severely- to moderately-distressed couples were treated with EFT. These couples’ mean pre-treatment DAS was 86.32, which rose to 100.14 post-treatment. At a four-month follow-up, the mean DAS had dropped to 92.05, which appears to show significant deterioration of the gains after therapy. One possible explanation of the deterioration in DAS after this follow-up period is that the initial DAS scores were relatively low compared to the previous studies. In fact, 57% of the couples in this study fell into the severely distressed category.

Johnson & Talitman (1997) studied thirty-four distressed couples and 79% of the couples receiving twelve 1.5 hours sessions of EFT reported improvement. The study calculated that the initial satisfaction ratings of the couples accounted for 12% of the variance at post-treatment. At a three-month follow-up, the percentage of the couples reporting improvement increased to 82%, with only 4% of the variance attributed to pre-treatment satisfaction (Byrne et al., 2004). Improvement also tracked the quality of therapist alliance, especially the perceived relevance of the treatment, older ages of the males in the couple, and the level of faith that the female in the couple had that the male still cared about her.

In Cloutier, Manion, Walker & Johnson (2002), sixteen couples with children who were chronically ill were given EFT and another sixteen couples from the same sample were put on a waitlist. Couples with a DAS of 110 or below were considered “distressed” because it has been suggested that this is an appropriate cutoff for parents with chronically ill children (p. 393). The mean DAS score increased from 99.15 to 108.38 at post-treatment. At a two-year follow up, the post-treatment DAS scores remained largely unchanged at 108.31, and the number of couples that had recovered from distress increased from two at post-treatment to seven at the two-year follow up. These numbers suggest that EFT may actually have a healing capability over time. However, it is possible that the improvement in marital distress over the two years may be related to natural adjustment to the chronically-ill status of their child or possibly a change in their child’s status.

Wood, Crane, Schaalje & Law (2005) undertook a meta-analysis of EFT studies from 1963 to 2002. These studies included several unpublished dissertations, such as Carlton (1978), Simms (1999), and James (1991), as well as the published studies of Hazelrigg, Cooper & Borduin (1987), Johnson & Greenberg (1985), and Goldman & Greenberg (1992). By converting marital satisfaction scores on the MAT, RMAT, KMSS and RDAS scores from prior studies to DAS scores, Wood et al. conclude that EFT showed the higher mean gains for couples with moderate marital distress than behavioral marital therapy and components of behavior marital therapy (e.g., communication training, etc.). All of these techniques, however, showed equal effectiveness for couples with mild marital distress.

MacIntosh & Johnson (2008) studied ten couples including at least one member that was a child sexual assault (“CSA”) victim with PTSD. To participate, the couples could not have any problems with drugs, suicide or violence, and at least one member of the couple had to score in the mild to severely distressed range. The majority of the couples “experienced severe, chronic and intrafamilial sexual abuse,” resulting in complex PTSD (p. 304). Both partners were victims of trauma in half of the couples. Despite this high level of trauma, half of the couples had clinically significant improvement or entered the non-distressed range after EFT treatment. Notably, all of the CSA victims experienced clinically significant reduction in traumatic symptoms as measured by the CAPS test and half experienced a reduction in traumatic symptoms as measured by the TSI test. This suggests that formation of a secure bond in the marriage may aid victims of trauma in non couples-related functioning.

In McLean et al. (2008), intermediate- to moderately-distressed couples with a partner diagnosed with advanced cancer were treated with EFT. The couples’ mean RDAS scores improved after treatment from 45.4 to 50.6 for the caregiver and 41.3 to 50.8 for the patient. At the three-month follow-up, the caregivers’ mean RDAS score improved even more to 50.9, while the patient’s score decreased slightly to 49.5. The study also found that symptoms of depression improved significantly through and beyond therapy, decreasing on the Beck Depression Inventory-II from 10.6 to 10.4 for the caregiver and from 19.6 to 16.4. At the three-month follow-up, these scores decreased even further to 8.4 and 14.1, respectively. Although this study shows immense improvements in marital distress and depression, these changes may also reflect the effect of time in dealing with the shock and adjustment of this terrible diagnosis.

Because EFT focuses on attachment, it has been suggested that it could be effective with insecurely attached couples in mid-marriage (Hollist & Miller, 2005), business-owning couples (Danes & Morgan, 2004), trauma victims (Johnson & Williams-Keeler, 1998), and for problems related to hypersexual behavior (Reid & Woolley, 2006). A secure attachment (Hollist & Miller, 2005) and tendency toward emotional abuse of the spouse (MacIntosh & Johnson, 2008, p. 305) have been considered contraindications.

Based on these studies, EFT appears to be an effective means of improving marital distress for moderately distressed couples and may even result in post-treatment gains. However, additional studies are suggested to determine the effectiveness of EFT on more severely distressed couples. The studies also suggest that EFT may be effective in creating a secure base for partners to deal with issues unrelated to their partnership, such as past trauma, terminal illness or chronically ill children.

Effectiveness of Process

A therapist’s two main goals in EFT are to: 1) access, deepen and distill experience of core emotions; and 2) alter negative interaction patterns (Johnson, 2007). This is done through empathic tracking and reflection, validating each person’s experience, evocative responding, heightening and interpreting, tracking interactions and restructuring key interactions (Johnson, 2007). Several studies have analyzed the effectiveness of EFT in meeting these goals and in determining the relationship of these goals to marital distress. In one study, videotapes of couples engaging in EFT were evaluated for: 1) level of experiencing; and 2) affiliative/autonomous responses in interactions (Johnson & Greenberg, 1988). Three couples with the greatest change in marital satisfaction through the course of therapy[2] (“high change couples”) from the earlier 1985 study were compared to the three couples with the least change in marital satisfaction (“low change couples”). Each of these couples designated sessions as their best sessions, and researchers evaluated portions of these videotapes. In this study, the high change couples were found to have a higher level of experiencing and a higher number of affiliative/autonomous responses in their interactions than the low change couples. “Softening responses,” where a previously critical partner is able to express vulnerability and request comfort and connection with the other partner, were particularly prevalent in the high change couples. This study indicates that success in EFT co-existed with the increased levels of experiencing and affiliative/autonomous responses, but this does not necessarily indicate a causal connection. For example, one would expect increases in marital satisfaction to go hand in hand with stronger affiliative statements, regardless of the type of therapy. The coexistence of a heightened level of experiencing, however, may be unique to EFT.

Greenberg et al. (1993) confirmed the findings from above and also found that couples treated with EFT experienced more shifts from hostility to affiliation than those on a waitlist. Specifically, “intimate, emotionally-laden self-disclosure…was more likely to lead to affiliated statements than other responses” (Johnson et al., 1999). They also found that “peak sessions” had more affiliative responses and more positive self-focused statements than positive other-focused statements. There were three times as many “hostile power” responses in poor sessions than in peak sessions and three times as many high emotional experiencing statements in peak sessions than in poor sessions.

Makinen & Johnson (2006) evaluated the best sessions of twenty-four couples with attachment injuries after EFT treatment on pain and forgiveness. It was found that “resolved” couples had a higher degree of forgiveness than “unresolved” couples, although emotional pain did not differ. Emotional pain decreased, however, in all of the couples over the time period of treatment. The “blamers” in the resolved couples were also found to have softened. Many of the unresolved couples had compound attachment injuries, such as multiple injuries or injuries to both partners.

These studies suggest that a partner’s emotionally-laden self-disclosure is tied to increased affiliated responses from the other partner. Both the level of emotional experiencing and the amount of affiliative responses appear to be tied to the success of EFT in increasing marital satisfaction in couples. Because an increased amount of affiliative responses would be expected when marital satisfaction increases, however, more studies are suggested to determine the causal connection theorized by EFT.

Conclusion

EFT continues to be one of the most empirically-supported forms of marital therapy in practice. It focuses on expression of core emotion between members of the couple and an understanding of the negative affect cycles that may exist within that context. By getting in touch with and expressing core emotions, including vulnerability, members of the couple may reestablish secure attachment within the relationship, which may even help them to deal with issues unrelated to the relationship. While many studies have been done to measure the effectiveness and process of EFT, additional studies to measure its efficacy with mildly- and severely-distressed couples are suggested.

____________________________________________________________

Rose Rigole, the author of this meta analysis, is an Emotionally Focused couples therapist with offices in West Los Angeles and Costa Mesa, California. For more information, please visit https://couplescalifornia.com.

References

Baucom, D., Shoham, V., Mueser, K., Daiuto, A., & Stickle, T. R. (1998). Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems [Electronic version].Journal of consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 53-88.

Byrne, M., Carr, A. & Clark, M. (2004). The efficacy of behavioral couples therapy and emotionally focused therapy for couple distress [Electronic version]. Contemporary Family Therapy, 26(4), 361-387.

Carstensen, L. L., Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1995). Emotional behavior in long-term marriage [Electronic version]. Psychology and Aging, 10(1), 140-149.

Cloutier, P. F., Manion, I. G., Walker, J. G., & Johnson, S. M. (2002). Emotionally focused interventions for couples with chronically ill children: A two-year follow-up [Electronic version]. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28, 391-398.

Danes, S. M. & Morgan, E. A. (2004). Family business-owning couples: An EFT view into their unique conflict culture [Electronic version]. Contemporary Family Therapy, 26(3), 241-260.

Dessaulles, A. (1991). The treatment of clinical depression in the context of marital distress. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa.

Goldman, A., & Greenberg, L. (1992). Comparison of integrated systemic and emotionally focused approaches to couples therapy [Electronic version]. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 962-969.

Gordon Walker, J., Johnson, S. M., Mannion, L., & Coutier, P. (1996). Emotionally focused marital interventions for couples with chronically ill children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1029-1036.

Gottman, J. (1993). A theory of marital dissolution and stability [Electronic version]. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 57-57.

Greenberg, L. S., Ford, C. L., Alden, L. S., & Johnson, S. M. (1993). In-session change in emotionally focused therapy [Electronic version]. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61(1), 78-84.

Hazelrigg, M. D., Cooper, H. M., & Borduin, C. M. (1987). Evaluating the effectiveness of family therapies: An integrative review and analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 388-395.

Hollist, C. S. & Miller, R. B. (2005). Perceptions of attachment style and marital quality in midlife marriage [Electronic version]. Family Relations, 54, 46-57.

James, P.S. (1991). Effects of a communication training component added to an emotionally focused couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 17, 263-275.

Johnson, S. M. (2007). The contribution of emotionally focused couples therapy [Electronic version]. J Contemp Psychother, 37, 47-52.

Johnson, S. & Greenberg, L. (1985). The differential effects of experiential and problem-solving interventions in resolving marital conflict [Electronic version]. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 175-184.

Johnson, S. M. & Greenberg, L. S. (1988). Relating process to outcome in marital therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 14, 175-183.

Johnson, S. M. & Greenman, P. S. (2006). The path to a secure bond: Emotionally focused couple therapy [Electronic version]. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 62(5), 597-609.

Johnson, S. M., Hunsley, J., Greenberg, L., & Shindler, D. (1999). Emotionally focused couples therapy: Status and challenges [Electronic version]. Journal of Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 67-79.

Johnson, S. & Talitman, E. (1997). Predictors of success in emotionally focused marital therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 23, 135-152.

Johnson, S. M. & Williams-Keeler, L. (1998). Creating healing relationships for couples dealing with trauma: The use of emotionally focused marital therapy [Electronic version]. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 24, 25-40.

MacIntosh, H. B. & Johnson, S. (2008). Emotionally focused therapy for couples and childhood sexual abuse survivors [Electronic version]. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(3), 298-315.

Makinen, J. A. & Johnson, S. M. (2006). Resolving attachment injuries in couples using emotionally focused therapy: Steps toward forgiveness and reconciliation [Electronic version]. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74(6), 1055-1064.

McLean, L. M., Jones, J. M., Rydall, A. C., Walsh, A., Esplen, M. J., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. M. (2008). A couples intervention for patients facing advanced cancer and their spouse caregivers: Outcomes of a pilot study [Electronic version]. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 1152-1156.

Reid, R. C. & Woolley, S. R. (2006). Using emotionally focused therapy for couples to resolve attachment ruptures created by hypersexual behavior [Electronic version]. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 13, 219-239.

Spanier, G. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15-28.

Wood, N. D., Crane, D. R., Schaalje, G. B., & Law, D. D. (2005). What works for whom: A meta-analytic review of marital and couples therapy in reference to marital distress [Electronic version]. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 33, 273-287.

[1] Most numbers based on meta-analysis provided in Byrne, Carr & Clark (2004); Johnson et al. (1999); and Baucom, Mueser, Shoham, Daiuto & Stickle (1998).

[2] As measured on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (“DAS”)